Suppose We See Ourselves

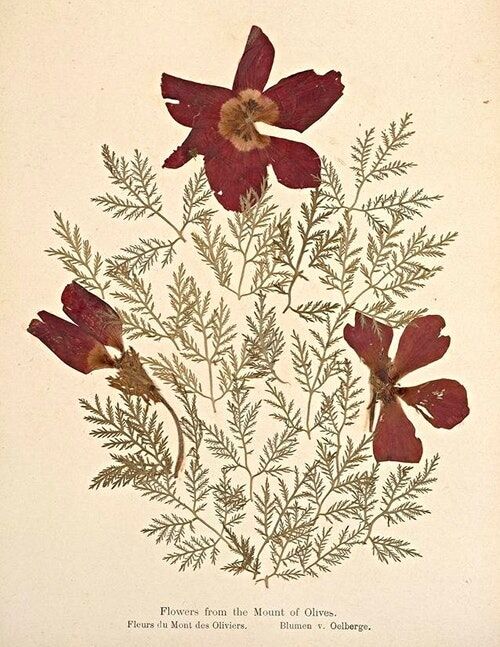

A list from the album Flowers and Pictures of the Holy Land, Boulos Meo (publisher), Jerusalem (source: The Getty)

Narrative form is often taken for granted, a set of storytelling rules that go unnoticed and unseen; similarly, colonialism benefits from an internal invisibility that resists observation. This autotheory essay considers the interplay between colonialism and invisibility, and explores how narrative form can act as a cultural intervention. The essay suggests that autoforms—such as autotheory, fictocriticism, autofiction, and autoethnography—expose invisible cultural rules and intrinsically alter the way content is understood. It is especially concerned with how colonialism uses authorship to limit internal observation and critique and suggests that by refiguring the ‘I’ and the ‘we,’ autoforms expose these invisible internal rules. It argues that autoforms actively reconfigure the boundaries around many of the early twenty-first century’s major cultural conversations about representation and appropriation, lived experience and expertise, and public space and private space, as well as notions of identity, othering, consciousness, and embodiment. The paper approaches form not just as narrative structure, but also as a tool, a technique, a strategy, and an intervention that inherently impacts content and changes how the cultural landscape is seen and navigated. Through comparing the yellow soils of southern Australia and Gaza, the grammar of Derrida and Wittgenstein, and the path of water and rivers, the essay explores how the form we use to tell stories is often as important as the content.

To link to this item: https://doi.org/10.35074/FJ.2024.78.75.002

Published: 30.03.2024

Publication type: Reflexive essay