The New Museum’s Personality: Digital Collecting as a Way to Democratize Museums

Museum collections are changing: curators have started collecting born-digital objects and shifted their research to focus on memes, social media collections, emojis, video games, etc. The nature of the museum object is transforming. In this essay, a digital curator of the Museum of London and a member of The Garage Journal's Advisory Board Foteini Aravani outlines the redefinition of curatorial research in the museum’s digital collections.

Real museums are places where time is transformed into space.

Orphan Pamuk

The Museum of London Is Moving

The Museum of London is preparing to move, in 2025, to a new building in West Smithfield (see Fig. 1). At the moment, it is undergoing a deep review of its collections, galleries, mission, the stories it tells, and its role in the lives of Londoners. We are focusing on democratizing our collections and diversifying our audiences. The upcoming move offers a genuine opportunity to transform our engagement and collecting practices, as well as the bricks and mortar of the building. At the Museum of London, we now have the opportunity to reinvent urban museums and make them relevant for the whole spectrum of society; to create an inclusive and inspiring public space, appealing to all visitors and crucial to facilitating their creativity. And this is an opportunity that is quite rare: curators usually work in established museums, with entrenched practices and procedures. So, this is a time when change can happen and new ideas can be born, when we can start doing things in a different way. This is an opportunity to change our research practices, to find new ways of curating, and to redefine the museum object.

Working at the new Museum of London has triggered a lot of thoughts and inspired a lot of debates and aspirations about what museums should be like in the twenty-first century: how they should behave, what they should offer. Not just the new Museum of London, but the new museum as a concept, as an entity.

The World Has Gone Digital. Don’t Museums Know That?

It has been a long time since the digital became part of our everyday life and started to be inherent in the way we create, produce, communicate, or share information. Artefacts have been created in a born-digital way for decades now. And yet, museums are still struggling with the idea of born-digital collections and intangible heritage, similar to how they were confused by the invasion of video and video art in the 1960s. Sometimes I feel that we are facing the same battle, but it is a bit trickier now, as digital culture is even more intangible and widespread than the medium of video or video art was then. At least, back in the 1960s, there was a tangible object, a video tape, that stored video content, which is why it was somewhat easier for museums to embrace this new cultural revolution: the ‘new’ object was as physical as a Roman urn or a manuscript. Nowadays, the digital object could be a tweet, a meme, a gif, an emoji, and anything in between.

In the museum world, we have been focusing so much on collections and objects, trying to excel at documenting, researching, and taking care of the artefact, that we forgot the most important thing: that we collect objects to reveal stories and share them with our audiences. It sometimes feels that curators get caught up in the object itself, detaching themselves from its heart and soul—its stories. In this era, defined by smartphones and social change, the new museum realizes that it is not just playing the role of a guardian of the past; it is embracing innovation and placing people at the core of its activities. The role of the curator has clearly been shifting for many years now, from an overprotective keeper of knowledge to an extrovert storyteller, for the new museum is not detached from society, sitting on the pedestal of its own authority. It is open and inviting, offering a socially engaged public platform that is designed for people and not only for objects. In other words, in order to define the new museum, we should take a step back and redefine the museum object. We should reassess what we collect, how we research and present it. We should rethink the role of the curator in the new museum.

Digital Collections at the Museum of London: A New Type of Collection—A New Type of Research

I started working at the Museum of London in 2015 as the curator of the digital collections. At the museum, we mean by the latter all collections that are created in a born-digital way: objects that have no physical surrogate, intangible and susceptible to technology obsolescence. The Museum of London tells the story (stories) of the city and its people. It takes care of more than two million objects in its collections, including dress, artefacts of social and working history, oral history, ephemera, and art, and holds the largest archaeological archive in the world. We are skilled in conserving and displaying artefacts. We have established policies for acquiring material culture and gathering personal histories in order to develop our understanding of the story of London from 450,000 BCE until the present day. Interpretation and display of these objects and narratives are the museum curators’ bread and butter. But now, we are being challenged to work and think differently. An ever-increasing amount of content, information, and data about the way we live in London is created, stored, disseminated, and networked in digital forms that add a different layer to the telling of the story of London.

When I came to work at the museum, I almost immediately decided to start a video games collection as a more engaging and immersive way of telling the story of London. We started collecting video games as objects of social history, focusing on either video games that were developed by Londoners, celebrating their contribution to the industry, or video games that depict London as an urban virtual space, in order to explore these representations or misrepresentations of the city in video game narratives over time. Speaking of opening up and democratizing our collections, I found it very interesting that accessioned objects in our collections had been developed in the bedrooms of 16-year-old boys in the 1980s on their Spectrum ZX computers, rather than by the multi-million game companies that monopolize the sector (see Fig. 2).

Collecting Social Media: Democratizing Collections

Museums have begun to explore collecting social media, realizing the importance of the power of the immediacy of events as they unfold, and of the collective memory that is disseminated over social media platforms. When museums collect tweets, they collect people’s voices and opinions, thus shifting the power of the creation of an object from an expert back to the community. So far, the conversation around the digital in museums has mainly focused on digital interpretation, digitization, digital marketing, and online collections. But over the past few decades, advancements in technology have changed society entirely. Every bit of information about world news, popular culture, and art is just a tap of a touchscreen away. So many aspects of the contemporary world are created in a born-digital way, which is why it is only a matter of time before museums have to face the issue of born-digital artefacts in their collections. The collectible has been reshaped and now includes a variety of things, from videos to web-based art, and museums have to tackle how to save this new form of cultural heritage. They have to do so now, before it gets lost forever. The challenge of born-digital objects consists in their impermanence and rapid obsolescence.

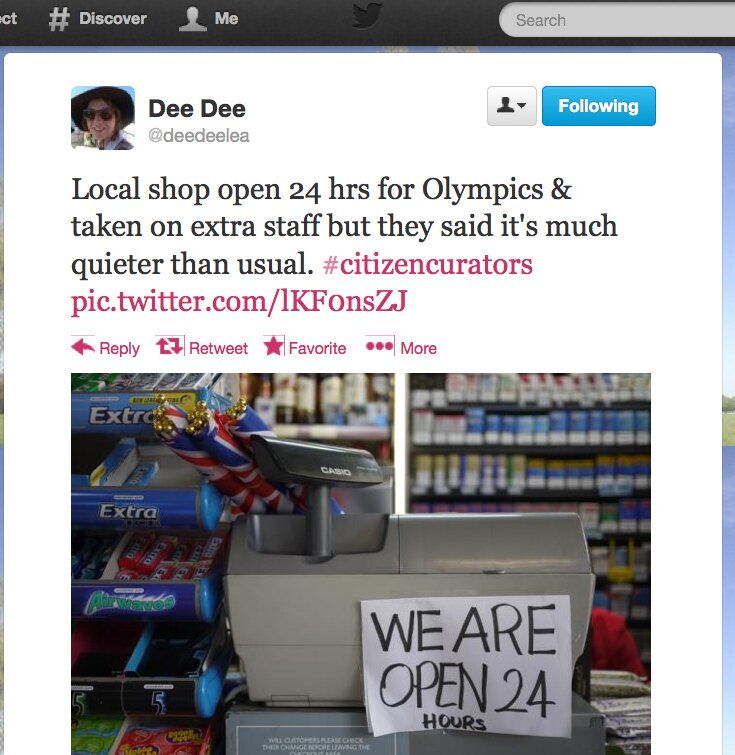

The Museum of London has been collecting social media—as a cultural artefact, an object of social history, and a way of documenting people’s voices—since 2012. The first social media collecting project was #Citizencurators: Life in London during the Olympics, which aimed to explore what life was like for a self-selected group of Twitter users living in London during the Olympic fortnight (27 July—12 August 2012). The London Olympics was identified as a major collecting area for the Museum of London because the subject had a local, regional, national, and international dimension for the city. #Citizencurators was devised as a pilot social media collecting project, part of the newly formed Digital Collections, and used the Olympic Games of 2012 on Twitter as a case study. The first aim of this project was to explore whether social media posts could be collected to record the immediacy of events during the Olympic fortnight. The impetus of the project was born out of the Museum of London’s not-so-rapid response to events in London’s recent history, such as the 7/7 bombings in 2005 and the summer riots of 2011, which limited our ability to record what happened and how the events immediately unfolded.

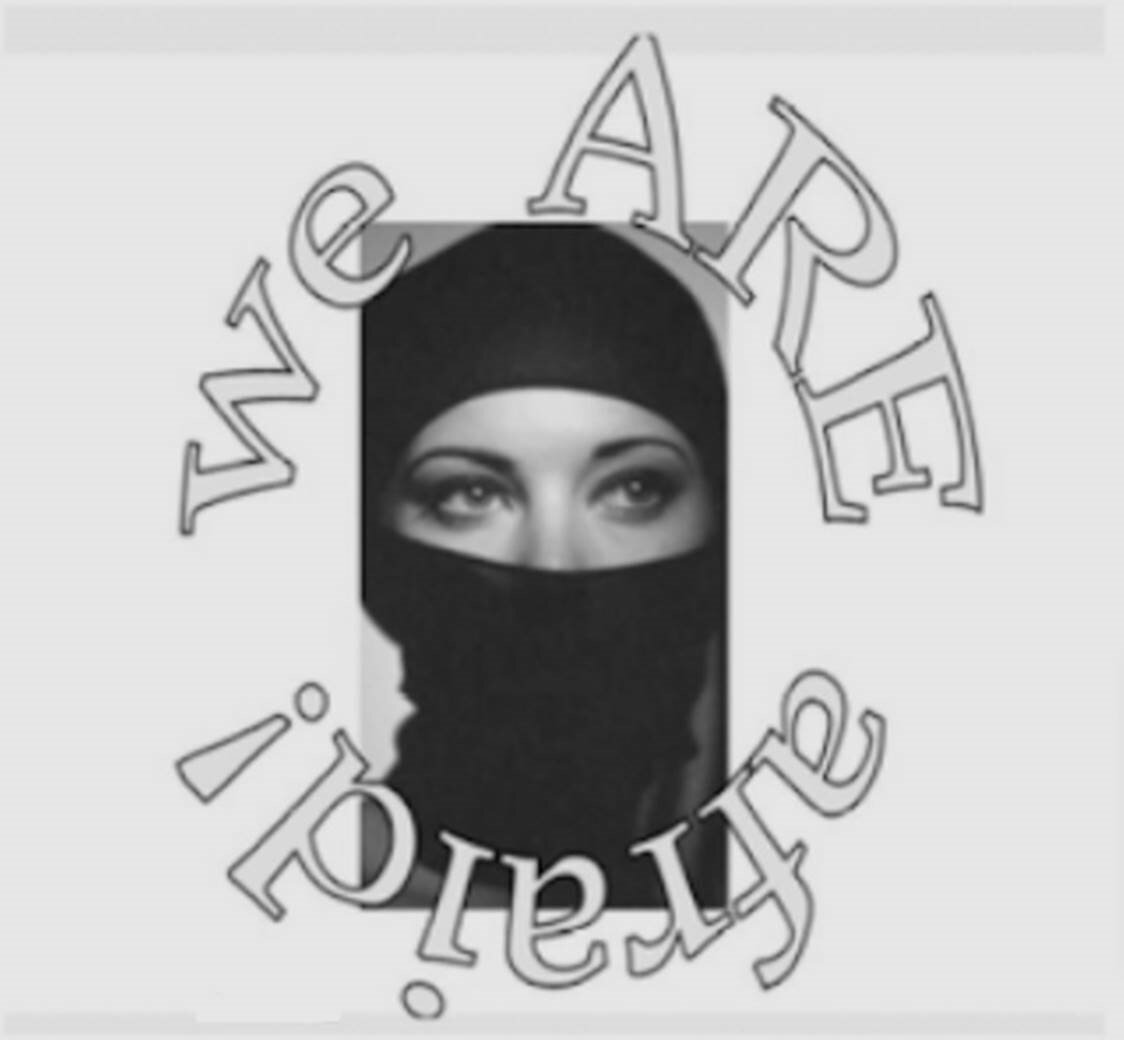

Flickr user @coconinoco, one week after the London bombings on the 7th of July 2005, rode the tube, giving out hundreds of these stickers (see Fig. 3). This image has been collected by the Museum of London in order to document @coconinoco’s contribution to a day of solidarity of Londoners after the bombing attacks. The aftermath of the 7/7 London bombings led to a boost of Islamophobia in the city. This is why we also collected @Samera’s image (see Fig. 4), to tell another side of the same story. When she posted this on the ‘wearenotafraid.com’ website, @Samera wrote: ‘This pic is to highlight my concern as an innocent Muslim and to raise awareness about the increase in racial hate crime because of the atrocity in London last week.’[1] There are different points of view to every history. These images, created in the times before the rise of social media in our lives, could even be considered precursors of memes.

It is often easier for a museum to collect objects that represent what happened after the event, as curators have time to understand the complexities and represent different perspectives and views about what happened in their collecting strategies. But how an event unfolds sometimes cannot captured retrospectively because the moment has been lost or the methods of communicating that information are not easily collectable. Secondly, could social media platforms, such as Twitter, provide a way of collecting alternative narratives about events and experiences—for instance, what was it like to live in London during the Games? The established narrative of the Olympics focuses on the experiences of athletes, participants, employees, and tourists. However, Londoners’ everyday experiences during the two weeks of the Olympics (a single mom in Stratford, a commuter who uses the Jubilee line of the London underground, or a resident of an apartment block partially occupied by the army to ensure the safety of the Olympic Games) may not be conveyed through physical objects or traditional media outlets. Thirdly, #Citizencurators was interested in the potential of social media to provide an alternative way of collecting that would challenge our existing collecting policy. By the end of the project, we had collected more than 8,500 tweets that documented the lived experience of Londoners during the Olympic Games of 2012 (see Fig. 5).

At the moment, I am revisiting the social media collecting practice at the Museum of London and exploring new areas of social media collecting, like memes, that could be potentially displayed in the Museum of London’s new home. Social media objects remind us that our responsibility is to curate meanings and tell stories that come out of the objects themselves. We are also reminded that, despite all our efforts and academic expertise, the stories we curate are better told by the people who lived them. Social media collecting proves that history has been and will always be in a state of flux, and that we, each one of us, are active players in its unfolding. It challenges the rhetoric of historical objectivity and authority that museums have championed, and brings people into the heart of the collections. Let’s also not forget the ephemerality of digital objects; the fact that they live online does not mean that they will stay there forever. For example, the two images above (see Fig. 3 and 4), collected around the 7/7 bombings in London, were posted on the ‘wearenotafraid.com’ website, which is no longer live on the web. So, collecting them means digitally preserving them for future generations.

The Museum as a Research Hub: Research in Social Media Collections

In March 2020, as part of a wider rapid-response collecting project around the experience of COVID-19 in London, we launched a social media collecting project called Going Viral. We wanted to identify and acquire tweets posted by Londoners during the first national lockdown, sharing their experiences of the pandemic in the city (see Fig. 6). The project followed on from the research report called History in the Tweeting published in August 2020 by Twitter UK, which identified seven behaviors that emerged or accelerated during the lockdown. The findings painted a picture of what people were experiencing and sharing digitally during that time. Social media interaction has been a intrinsic shared experience for millions during the COVID-19 crisis, which may have long-term effects on the way personal and professional communities connect.

Humor and sarcasm have always been an inherent characteristic of Londoners and are especially often employed as coping mechanisms in times of crisis and hardship. The COVID-19 pandemic has been no different, with imagination, creativity, and wit uniting us in ways never seen before while we have been physically separated by social distancing measures. At the Museum of London, we decided to focus on tweets (as Twitter first coined the term ‘going viral’) and tried to identify content that was ‘shared’ or ‘liked’ by at least 30,000 different people, creating a vital virtual form of camaraderie between Londoners during the lockdown. In a year when we were forced to be physically distant, people came together virtually on Twitter. The tweets collected by the Museum of London capture how a sense of humor and a true sense of community helped people in London cope with the pandemic and support each other.

These 20 tweets (see Fig. 6 for a taste of them) were collected, in collaboration with Twitter, as screenshots—static basic images. The screenshots recreate the look and feel of the viral tweet, but, of course, they do not reflect Twitter’s environment, the dynamic nature of the platform, its interactivity, comments, etc. The tweets were acquired as a snapshot in time, with the context and the platform’s characteristics removed. It is definitely not the best approach to the accession of tweets to a museum collection, but it is a short-term solution that is meant to work until we explore new possibilities of accessioning tweets on Twitter, a format that would respect their provenance and preserve the platform’s interactivity.

My research in the years to come will focus on collecting social media, not limited to Twitter, but expanding to encompass other platforms, too. I want to investigate ways of simulating social media platforms in order to respect the authenticity of the collected object and preserve it for future generations. This way, research in the social media collections will be more complete. The tweets that the Museum of London has collected come with consent and reuse permissions from the users who posted them: ethical issues around these collections should always be taken into consideration.

The rapid rise in the use of social media to document events of historical significance presents a great opportunity to museums that seek to rethink their collections. People have been capturing their participation in historical events on social media for almost a decade now. This tendency presents researchers with new opportunities to engage with the content generated by social media platforms. Twitter has proved to be one of the most important tools used in social activism. While such digital content adds a new layer of documentary evidence that is immensely valuable to those interested in documenting, researching, and interpreting contemporary events, it also presents significant archiving, data management, and ethical challenges for curators (Bergis, Summer and Mitchell 2018).

ICOM’s New Definition of the Museum

On the 7th of September 2019, I attended one of the most fascinating conversations in the museum field, the debate on the new definition of the museum at the 25th International Council of Museums (ICOM) General Conference in Kyoto (see Fig. 7). ICOM’s museum definition was first established over 70 years ago, with minor tweaks over the years, and describes the museum as ‘a non-profit, permanent institution in the service of society and its development, open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates, and exhibits the tangible and intangible heritage of humanity and its environment for the purposes of education, study, and enjoyment’ (ICOM UK n.d.). This current version of the definition was established in 2007 and was adopted by the 22nd ICOM General Assembly in Vienna. The first definition from 1946, which was included in ICOM’s initial constitution, states that ‘the word “museums” includes all collections open to the public, of artistic, technical, scientific, historical or archaeological material, including zoos and botanical gardens, but excluding libraries, except in so far as they maintain permanent exhibition rooms’ (Salguero 2020). Between these two definitions, from 1946 and from 2007, I personally cannot see a lot of ideological change or progress in the concept of the museum.

Jette Sandahl, the founding director of the Women's Museum of Denmark and the Museum of World Culture in Gothenburg, led ICOM’s commission on developing a new definition, suggesting that the current one ‘does not speak the language of the twenty-first century’ by ignoring demands of ‘cultural democracy.’ Her amended concept of the museum, presented and discussed in 2019 in Kyoto, reads:

‘Museums are democratising, inclusive and polyphonic spaces for critical dialogue about the pasts and the futures. Acknowledging and addressing the conflicts and challenges of the present, they hold artifacts and specimens in trust for society, safeguard diverse memories for future generations and guarantee equal rights and equal access to heritage for all people.

Museums are not for profit. They are participatory and transparent, and work in active partnership with and for diverse communities to collect, preserve, research, interpret, exhibit, and enhance understandings of the world, aiming to contribute to human dignity and social justice, global equality and planetary wellbeing’ (ICOM 2019).

This is the first time that such a radical, political, and different definition has been proposed by ICOM. The definition sparked the most passionate and engaged debate I have ever experienced in the museum world, and it was agreed to postpone the vote on the proposed definition. The debate was really between the more traditional colleagues and the younger generation who see the role of the curator changing, and between the Western and non-Western schools of thought that look at the role of the museum through different prisms. The old definition does not speak the language of our times; it does not respond to the current challenges that demand cultural democracy, historic transparency, and an increase in diversity and inclusion. I felt that the debate was not just a disagreement in the phrasing of the new definition of the museum: it unveiled the difference in opinions around the new museum.

What is the Personality of the New Museum?

This is me, painting the picture of the new museum in the twenty-first century the way I envision it. This vision is not strictly related to the new Museum of London, so when I am mentioning the new museum, I am talking about the ideal version of it, one that I have imagined based on my aspirations and curatorial research.

The new museum is not complete.

It always evolves and changes, the way life does. It is a living organism in sync with society, and the curatorial thinking and practice should be flexible and adaptable to the changes that are happening or about to happen, only to be complimented by visitors’ connections and narratives.

The new museum is a bridge within and beyond society.

Objects will always populate museums, but visitors will not. We need to find new, interesting ways to attract them.

The new museum is bold.

It says the things we want ourselves to say. It is straightforward, very opinionated, and does not hide history, difficult stories or awkward encounters. There is a brutal honesty in the narratives of the new museum that does not shock us; it makes us think, moves us, and prompts us to understand the world around us.

The new museum is sassy, and curious, and by no means neutral.

This idea of neutrality in museum institutions is very much informed by the Enlightenment era and the idea that Eurocentric Western scholarship produces universal knowledge relevant everywhere (Kwaymullina 2016). This notion portrays Western scholars as speaking from a neutral position, which means that those outside it are biased. But the new museum takes risks; it is very straightforward and not afraid to tell difficult stories, confront colonialism, and challenge institutional memory. The new museum is democratizing its collections by questioning authorship and ownership.

Importantly, this democratization is boosted by the digital, by the way digital technologies have taken over every aspect of our life. We create using the digital, we communicate using digital platforms, we tell stories and share our opinions on digital channels. The digital revolution has reshaped the collectible, has changed the museum object: how it is created and, most importantly, by whom.

The new museum is willing to open up its collections and allow people to come in and relate to them through different readings and narratives.

Bibliography

- Bergis J, Summer E, and Mitchell V (2018) Ethical Considerations for Archiving Social Media Content Generated by Contemporary Social Movements: Challenges, Opportunities, and Recommendations. Documenting the Now, docnow.io/docs/docnow-whitepaper-2018.pdf (07.19.21).

- ICOM (2019, July 25) ICOM announces the alternative museum definition that will be subject to a vote. icom.museum/en/news/icom-announces-the-alternative-museum-definition-that-will-be-subject-to-a-vote (accessed 19.07.21).

- ICOM UK (n.d.) ICOM Definition of a Museum. uk.icom.museum/about-us/icom-definition-of-a-museum (07.22.2021).

- Kwaymullina A (2016) Research, ethics and Indigenous peoples: An Australian Indigenous perspective on three threshold considerations for respectful engagement. AlterNative 12 (4): 437–449.

- Salguero B (2020, May 22) Defining the Museum: Struggling with a New Identity. Curator, curatorjournal.org/virtual-issues/defining-the-museum (07.22.2021).

- Twitter UK (2020, August) History in the Tweeting. Online report, marketing.twitter.com/en_gb/collections/history-in-the-tweeting (07.19.21).

Footnotes:

1. The web archived version of the website used to be accessible via the Wayback Machine at web.archive.org/web/20070331221148/http://www.wearenotafraid.com, but not anymore. Just another example of the ephemerality of digital objects.

Author’s bio

Foteini Aravani is a digital curator at The Museum of London. Having started the museum’s collection of video games in 2015, her research practice has currently focused on social media collecting. She has curated a range of exhibitions and displays at the museum, including ‘The City Is Ours: A Tale of Two Cities’ (2017) and ‘London Visions’ (2019). She previously worked at the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Athens; the British Library and Battersea Arts Centre, both in London. She is a member of the jury panel for the Lumen Prize, an international award for art created with technology.