Artists Strike Against Art Institutions: A Symbolic Gesture Or a Strategic Action? A Conversation between Sasha Pevak and Katja Praznik

In this conversation, Sasha Pevak and Katja Praznik discuss their common interest in the struggle for the improvement of working conditions in the arts, and, more broadly, why we should consider the work we do in the arts as a form of labor. Touching upon the two participants' professional backgrounds and also upon the shared cultural awareness of labor in socialist contexts, the conversation is raising the questions of how to surpass the ongoing contradictory situation in the art systems that largely continue to exploit the labor of art workers while at the same time enjoying, at least in some areas, the image of being politically progressive and ethical.

Katja Praznik: The fact that I come from a socialist background had an impact on why I started to work on labor issues in the arts because historically labor in socialist Yugoslavia was treated differently than in capitalist societies and from how it is treated today in a post-Yugoslav world. There was a cultural and a political awareness about the importance of work and labor rights and this legacy is a significant anchor for my work. When I still worked in Slovenia in an association that gathered freelance art workers and independent cultural NGOs (Asociacija), we raised the question of fair payment in the arts, which was packaged in the larger context of improving the working conditions on the independent art scene in the new nation state of Slovenia. But the majority of artists didn't want to talk about themselves as workers, that was one of the main issues.

Then, when I moved to the United States in 2012, I learned early on about W.A.G.E. (Working Artist and the Greater Economy), a New York–based art workers/activist collective. I was shocked but also positively surprised by the paradoxical situation. While I have a socialist background and come from a country which used to define itself as a ‘country of the working people,’ the artists there have a problem thinking about themselves as workers. But when I came to the belly of the (capitalist) beast —the U.S.—there I found artists talking about themselves as workers and being acutely aware that what they do is labor that needs to be paid. Readers based in the territories that once were socialist states may relate to this sentiment. For example, Russia was once the epitome of socialism, but it would not surprise me if a similar reluctance or aversion to labor rights discourse has emerged after the end of Soviet socialism. At any rate, the sentiment or feeling will, of course, be very different because the experiences of Yugoslav and Soviet socialism were not the same. In fact, it is important to note that there are a variety of historical forms of socialist states and the aftermaths of their dismantling are similar but also different. Nonetheless, I thought it is important to note the legacy of Yugoslav socialism which, while different from the U.S.S.R. version of socialism, has a profound impact on my politics. It may also be interesting to know more about this, as your career is very dynamic, and you shift between different contexts.

What made you think about these questions and is there a common thread that underpins them? If you could situate your knowledge, where would you situate it, considering that you changed the environment a lot?

Sasha Pevak: I originally come from Russia and Ukraine, but I was mostly professionally formed in the Western Europe and in France. I researched the question of art systems in the U.S.S.R. and Russia during my PhD, and I work with the institutions, individuals, and collectives coming from the ‘post-Soviet’ countries. I am thus aware of how the art system and the state support functioned there in the past, also how it was intertwined with the ideology, and how it works today. To summarize very briefly, in post-Soviet Russia, the socialist past and experience were rather seen as a burden because of the associations that were made between socialism and totalitarianism; and speaking about arts—because of this tie between art and ideology. Thus, not everyone of course, but a large part of Russian society after the dissolution of the U.S.S.R. was tending to obliviate the socialist experience, often praising liberty and flexibility in terms of economy, labor laws, arts, etc. This knowledge and cultural awareness of the Soviet experience, of its Russian neoliberal heir, and of the French historical engagement and struggle for labor rights and social security were simultaneously nourishing my research and opinions.

Another point through which I approached the question of art workers' labor came from practical analysis of contemporary art mechanisms, when I was looking at how different types of art labor are quantified, contractualized, and treated, and what place different categories of art workers occupy in the power hierarchy of the art systems. For instance, I concluded that what we call ‘curatorial work,’ even in the case of independent curators, is rather easily quantified by institutions, and a curator often finds themself in a position of certain power, at least towards artists. While artistic labor, which largely consists of seemingly non-productive activities like theoretical and practical research, visual tests, and other activities that artists ‘do for themselves,’ is much more hardly quantifiable and most often neglected by the institution of contemporary art.

KP: You are laying out a number of terms: art worker, artist, curator, labor. When we talk about art, one of the main issues is that art work appears hard to quantify and that is because whatever artists do is not considered work, at most it is an act of creation. Art work supposedly stems from artists’ need for self-expression, they do it for love, and so on. A lot of other professions that are connected to the ‘work of art’ (object) but not to ‘art work’ (activity) also participate in emphasizing the exceptionality, the talent, the creativity, rather than considering this activity as a form of work. So perhaps artists do work, but cultural perceptions about art as a form of labor go against this notion.

While we all ‘work,’ there's also the question of ‘labor.’ If we turn to a completely different discourse, not the discourse of aesthetics, and if we look at the issue of art work from the point of view of labor legislation, of international labor rights regulation, all these questions become very different. On the one hand, labor entails workers’ rights and labor protection. Work, on the other hand, is a more general, abstract term and it does not necessarily entail these kinds of protections. When we consider these two terms in the context of a contemporary art museum or in the institution of Western art in general, things become confusing. For example, we have art workers who are employees in a museum and, depending on the context, a European country or the U.S., labor rights of these employees are more or less protected. In the U.S., the labor rights legislation is extremely weak to non-existent, but in the European context the labor rights legislation is better defined, for example, with collective bargaining agreements. However, the labor rights protections and legislation rarely extend to those art workers who are not employees but work freelance or independently. In the European context they are often treated as self-employed, which brings on a host of issues. Matters become problematic because the protection of workers’ rights is attached to employment and not to the fact that one works. This becomes most explicit when we consider artists who are not really employed in museums and museums also don't consider them as employees.

Curators, on the other hand, can be employed in museums and may have rights based on their employment status. Perhaps it will be interesting to the readers to point out a recent outcry of museum workers in the U.S., a kind of rebellion of museum art workers regarding unfair payment and salary transparency. Anonymous museum workers created a public Google spreadsheet to establish salary transparency and to demand fairer payment and working conditions. Unionization of museum workers has thus been a rising trend in the U.S. art museums, however, the problems with working conditions of freelance art workers remains and artists are really the weakest and most exploited players in the system. So, we see that museums play a pivotal role in reproducing labor exploitation, especially the actors of the upper management structures who are positioned at the hierarchical top. They do not seem to see the benefit of protecting labor rights, fair payment, or good and fair working conditions. They are much more invested in maintaining the status quo and in relying on the ideology of aesthetics, which has historically produced and to this day reproduces the idea that art is not work. For example, art workers in Slovenia have been protesting for years that contemporary art museums and galleries pay them the legally required exhibition fees, which are in fact symbolic amounts. Directors of these institutions, some of them internationally recognized curators, have not responded in any politically positive way to the demands. Instead, they assume the role of a victim of the system rather than accept the responsibility and the power they have and the possibility to do things differently. For instance, I have collaborated with an artist who was invited to hold a solo exhibition in a Ljubljana-based public gallery. His fee represented merely 1% of the entire budget. When I pointed this out in a text for the exhibition catalogue, the director was offended but nobody thought to resolve the issue by raising the fee. As a professor who teaches future arts managers, I realize that being an art museum director is no small feat, but one can always decide to apply more equitable standards and respect and enforce labor rights for artists and art workers. In an effort to change the practice of non-payment so pervasive in the art world, I have recently started an initiative called a Cultural Work Inspection where art workers are welcome to write (anonymously, if they wish) about similar exploitative situations they are encountering. The aim is to make the exploitative practice more visible and tangible and to use the stories to derive further political demands.

SP: It is indeed essential to identify and clarify the terms that we use in relation to art workers’ labor, as some of them serve to perpetuate exploitative practices and the myths through which they are justified; we need to research the history of the concepts that stand behind them to understand how they were formed, operated, and continue to operate.

First of all, the term ‘independent’ seems questionable to me both symbolically and strategically, because I sincerely do not know what non-contractualized art workers are independent of, if not of dignified working and living conditions and of potential forms of collectivity. I find more relevant the use of the term ‘interdependent’ that I first saw employed by the curator Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez. It creates an image of interrelated collectivity instead of what could be a pretended independence, but in reality—neoliberal entrepreneurship, competitiveness, and atomization, that ‘independent,’ in my opinion, suggests; an interesting text on this subject has been recently published by a researcher and curator Kuba Szreder (http://artsoftheworkingclass.org/text/interdependent-curating). It is also important to question the term ‘support’ because it perpetuates the logic of reward for an activity that is not considered labor, while what we are looking to do here is, as you said, to bring art work back to the sphere of labor. A manifesto in this regard entitled Let's not “support” artists, let's remunerate art workers! was issued and signed by the collectives La Buse and L'Œuvrière, the unions STAA and SNAPcgt, and art workers in May 2021 (https://blogs.mediapart.fr/les-invites-de-mediapart/blog/110521/ne-soutenons-pas-les-artistes-remunerons-les-travailleuses-et-travailleurs-de-lart). It states that the actual mechanisms of support rely on a limiting definition of work, separating principal (or productive) activities and accessory (non-productive) ones. By consequence, they perpetuate existing inequalities, whether they are economic, social, or symbolic. And finally, I use the term ‘art worker’ to encompass all the categories of workers involved in the field of arts. Through this operation, I am trying—at first discursively, but also in the long term politically—to bring them together under the same umbrella rather than atomizing them into separate groups with distinct interests. Because if we look at historical examples, atomization was often used to break art workers into separate groups with separate struggles. The result was one group benefitting from more advantages than the other one.

Let us look at the French example, where today we find two distinct legal statuses for visual arts and writing and for performing artists, artist-author (artiste-auteur) and entertaining worker (intermittent du spectacle) respectively—this case is examined by the French writers Mathieu Grégoire in Les intermittents du spectacle. Enjeux d’un siècle de luttes (2013) and Aurélien Catin in Notre condition. Essai sur le salaire artistique au travail (2020). According to them, the workers of performing arts quickly grasped the idea that it was essential to go beyond the particularities of the profession in order to unite at the inter-professional level and to go beyond the limits of their sector, inscribing their struggle in a larger context of labors’ rights mobilizations in the twentieth century. This gave to intermittents du spectacle a big number of social advantages, such as unemployment allowance, sickness leave, and maternity leave. While as Catin suggests, artists and writers were unable to obtain the same level of structuration because ‘the foundations of intellectual property induce individualism. They compete to hide the richness of the work by projecting the figure of the isolated creator, a sort of Robinson of the mind collecting the fruit of their genius’ (Catin 2020: 38). There were also basic economic reasons for that. The avant-garde of art after the Second World War in France was mostly formed by artists coming from privileged social classes, and it was more advantageous to them to continue to get paid via invoices and royalties rather than contribute to the general security support for simple economic reasons. They were nourished by and were nourishing the idea of individual success, and thus, as the examples evoked by Catin show, certain artists were consciously opposing social security advantages because it was better for them economically to remain independent entities, while sales were the only possible way of legitimation of their work.

If we come back to the socialist countries, the Yugoslavian example seems to be rather an exception in this context. The arts system in the U.S.S.R. was based on the principle of unions. The Union of artists, for example, was a state-run and the only official organization which authorized artists to exercise their activities. Otherwise, they had difficulties working (if artists managed to practice but were unemployed, they were considered ‘parasites’ by the state) or exhibiting as artists officially. A membership in the Union of artists provided them with dignified and comfortable living and working conditions: a decent salary, materials, a studio, social security, and others. However, all this came along with a certain number of constraints, including the ideological pressure on the level of aesthetics and ideas, censorship, and political repression. Because of this experience and the tie between art and ideology, the idea of the role of the state in culture (as well as in many other spheres of life) was profoundly corrupted during this period. This is surely one of the reasons why in contemporary Russia the diversity of private institutions is very much praised, as they supposedly give a guarantee for independence from the state, for freedom, and for a multitude of voices (even though state-funded unions survived in Russia, their role is strongly reduced if we compare it with the Soviet times).

KP: That is what is also interesting in socialist Yugoslavia: the level of freedom in terms of what artists could do and what kind of topics they raised was very different. I think therein lies the distinction of the Yugoslav form of socialism, of self-managed socialism—the oppositional movements were articulated more freely in a certain period, but that freedom also changed during the 1970s and 1980s. However, I think it is a huge problem globally that people think there is such a thing as ‘Eastern Europe’ and that it is a homogeneous space, and that people think about the socialist context as a homogeneous space. There was a huge difference if you were an artist in the U.S.S.R., and if you were an artist in socialist Yugoslavia and if you were an artist in socialist Hungary and so on.

There is a common thread about this relationship to the state which is very ideologically burdened because neoliberal ideology deconstructed the welfare state. And this is also why we talk about neoliberalism as a political form that demonized the state, even though neoliberalism in fact repurposed the role of the state, in the sense that the state is no longer protecting citizens’ labor rights and securing welfare protection. In neoliberalism the state is transformed so that it deregulates these rights while it implements competition and market logic. The state is now an investor, it functions as an enterprise, and when the state becomes an enterprise rather than an entity which protects its citizens, we have a problem.

However, in the territories that were historically socialist, the state is demonized for a different reason: because it was apparently too overarching or repressive. This is a historical myth which is often presented one-sidedly because it is not in the interest of the neoliberal powers to consider that the state had a positive role. It is important to recognize that the state is not merely a sum of repressive apparatuses, there are also institutions of common/public social reproduction, such as the healthcare, retirement, education systems. The criticism of historical socialism often tends to forget this distinction.

SP: We both have teaching positions at universities or art schools. How are these questions perceived by your students? What feedback did you receive during your courses?

KP: I teach in an arts management program where the majority of students in the program are not necessarily artists, but some of them are and they come to the arts management program because they are often aware that as artists it's going to be very hard for them to make a living and they wish to have a bit of a broader understanding about the artworld and other possibilities there are to work in the arts. In my classes I address the problem of artworld as a site of exploitation and I point out the ways in which this is visible from the viewpoint that art is not considered as a form of labor. While the students I teach will probably end up working in a development, fundraising, or PR department in a museum, or run a nonprofit theater and so on, I always tell them ‘whatever you do, your work, your labor has to be a line in a budget.’ In other words, I urge them ‘not to make a budget without including the cost of your labor.’ I consider these students to be the next new generation of cultural managers and I want to count on them that they will not contribute to or reproduce (self)exploitation. Other students from art departments in the college also occasionally attend my classes and I like to ask them why they decided to take the courses I teach. The usual reply is, ‘well, because I want to learn about the other side,’ by which they mean funding. However, in this package that contains the larger context of the arts including its economy, they also get acquainted with the idea that art is and should be a form of paid labor. I like to emphasize that we need to look at art not just on the level of content, that is what you see when you go to a museum or a gallery or what you experience when you read a great novel or a poem, or you go to a concert, or you see a great street art or other kinds of performances, or a film. This is all great of course, but all that we experience as people who love art and who enjoy and who appreciate art also takes place in a particular socio-economic and political environment. And the economic environment of Western art and culture is completely mystified. In my classes I take time to deconstruct the mystification of art from various angles. While I do that in the context of an arts management program, for me the real change will take place when art schools are going to start talking about this economic environment and not mystify it with the help of the neoliberal ideology of entrepreneurship, according to which all you need is creativity and love. If we want to make the idea of art work available to all people and not just the ones that can afford it because they are either born in rich families or have inherited wealth, then we need to start talking about the economic relations of art production, and this is something that you rarely find in art schools. Or, if you do, it is mystified by the ideology of entrepreneurship, which is also extremely problematic because it gives students and future artists fake promises in terms of how they will succeed based on their talents/creativity. Again, because the economy is not accurately discussed or presented.

SP: The situation in France is a bit specific because education—in theory—is accessible: it is almost free, so even if you come from a disadvantaged background you can benefit from it. In practice, things are a little bit different, because if one wishes to start a degree at an art school, in order to succeed in the exam, they systematically need to spend an additional year in preparatory classes, which are found not in every city and are very often privately run and thus must be paid for. However, higher education in arts in general remains very much accessible, especially if we compare it to the situation in the United States or the Russian Federation. This explains to me why a lot of students that I worked with are completely conscious and politically aware of the material conditions of living and of working in the arts. I was excited to find out that the students were actively confronting the institutions (for example during the occupation and mobilization movement of cultural institutions that started in France in March 2021 and to which occupation of art schools joined, https://www.franceculture.fr/emissions/journal-de-8-h/journal-de-8h-du-mercredi-10-mars-2021), and questioning the education and cultural systems in regards of art workers’ labor, among others.

There were of course some interesting individual reactions to this movement, but in general the institutions were unable to give adequate responses. Again, probably because of the persistent mystification of artistic labor, according to which art must not be smeared by such things as money, thus, in order to protect the purity of artistic work artists should not be preoccupied by the economy during studies. Another myth I observed was that the artists were always suffering but were finding their way in the end: ‘nobody has ever been prepared for this, but I figured it out by myself; and you will do so too.’

On a more positive side, this consciousness about material conditions of art labor among students created brilliant examples of collectivity and solidarity. The movement of mobilization has touched a big number of French art schools and the actions of the students were commonly coordinated. This moment has also given place to the emergence of many visual forms, a conceptual reflection on the relation between artistic labor and other forms of labor—for example, sex work that is also unrecognized in France. Most of the people I met or worked with were completely conscious about the fact that the effort must be collective, that at a certain point one must leave their individual ambition aside and stand with the others in a united front.

KP: I was recently involved in an international workshop Artfield as Battlefield in Belgrade, Serbia on establishing artists' fees and a more equitable environment and better working conditions in the arts. So, the context of France in relation to these issues is interesting because there the cultural idea of labor rights is still present. I think that one of the most important demystifications in the arts is precisely to set aside this idea of exceptionality of doing art work for the love of art and because you love what you do and find it meaningful. Many other kinds of professions have a sense of importance (for example, medical professions, education etc.) but that does not mean that they accept to be exploited on this basis. While there can be state-enforced laws and rules that protect one from being exploited, in the absence of these kinds of laws it is on us and on our and your ability to recognize that we may do extremely interesting work, yet we are at the same time exploited. Until we decide that we are exploited and start calling things by their name, we are not going to get out of this circle that Pierre Bourdieu termed ‘disavowed economy of the arts’ and that I call exploitative economy of the arts.

I strongly believe in the power of collective power of artists and art workers, especially in the era of neoliberal ideology where competition is so emphasized that art workers see their peers as competition. While I have nothing against distinguishing different kinds, levels, and quality of art and ideas, I cannot support the system that uses it for exploitation of art workers. I'm always thrilled to hear about collective action of art workers, especially if they understand that exploitation is what they rebel against. We may be great, avant-garde, exceptional in many ways, but we don't have to be exploited—we are the ones that have to say no to this exploitation and we have to be very militant about it. As united art workers we say no to exploitation of our labor. The use of ‘art work’ is therefore politically strategic. For instance, in the workshop I attended, a member of an Italian collective Art Workers Italy said they purposefully write and talk about ‘art work,’ that is two words, which implies the activity, not the object or end result. I find it tremendously important that the process of the activity is emphasized and that the notion is strategically used. As such, the use of the words art work and art workers becomes a political tool to rebel against exploitation of labor while we do what we love.

SP: Historians, thinkers, and activists remind us all the time that social rights and labor rights are negotiable. It is not something that is given once and for all, but it is a space for negotiation and for social struggle.

KP: I totally agree, we are the ones fighting for these rights. For example, as educators, you and I, we can do a lot of work by informing students and making sure they are aware of the economic aspects and labor rights in the arts. It is important for the new generations of art workers to know the history and to be aware of the historical examples of labor rights in the arts along with a critical analysis that helps them to understand what was, for example, good in socialism and what didn’t work and why. Every historical example offers aspects that are positive and those that had problematic effects—why not take the good and understand what the problem was with the negative consequences, and then build from there. After all, the idea is to stop the exploitation in the arts. And if I now throw the ball to the high court of the museum directors: what are they going to do about the exploitation? How are they going to reconcile the declarations about progressive socially critical contemporary museums and the exploitation of art workers? Where are they on the map of being anti-exploitation of art workers? Are they merely talking the talk and selling progressive ideology, or will they walk the walk?

SP: In your works, you often refer to a historical example of Goran Đorđević, who in 1979, in the context of socialist Yugoslavia, issued a call for an International Strike of Artists? He was advocating for a general strike of any artistic production, for the boycott of the system of art that he saw as repressive, exploitative, and alienating. He invited numerous international artists to take part in it. However, he received about forty responses, most of which were negative. Why, in your opinion, the actual strike did not take place?

KP: I think this is a telling historical example. Why didn't Djordjević’s call for an international strike of artists in the late 1970s generate an actual strike? Let me answer bluntly: because there is not enough militancy in the art world. If we don't consider the art world as a system that is exploitative and if we want to be part of this system because we think that perhaps we are going to make it, then we are supporting and reproducing an exploitative system. If we don't recognize our position in the art world as exploited, then we also can’t go on strike. The question here becomes: why do artists need museums? Do they really need them? It’s a question of power and how you define these relations of power and the power of boycott. I think that the strike proposed by Djordjević didn't generate an actual strike because the majority of art workers don't want to question the Western system of the arts as a system that is (also) reproducing forms of exploitation. If we ignore the enormous amounts of exploitation going on in the art world, then the strike is unlikely to happen because there's too much mystification and too many illusions.

SP: I am also asking myself: who can actually afford a real strike today? It is sometimes hard to blame those individuals and collectives who do not openly confront institutions on the question of labor, because paradoxically it is very risky, economically speaking. As long as there is no generalized support of art workers, it is hard to claim your own opinion and struggle for your rights, because you simply won’t be invited next time, or you can become a persona non grata in certain circles. This might also mean that you will be isolated and that your political engagement will no longer serve anyone and that your voice will not be heard anymore. This is why being ‘independent’ doesn’t actually guarantee your freedom at all, rather the contrary.

KP: While I understand that, I think there is a certain level of labor militancy that is lacking in the art world. An undocumented migrant worker can be economically exploited in a similar way an art worker can be exploited in the art world. Both (migrant worker and an artist) are driven by love either for their families or for art and both often end up doing the work without fair payment. Certainly, there is a difference in their social and safety networks and there is a difference in the motivation and intensity of the exploitation they endure, but as far as the lack of fairness or payment is concerned the two worlds coincide. It's just that one worker sees and recognizes the exploitation while the other one thinks: my work is meaningful etc. I'm only doing it for free or low pay but eventually I’m going to make it in the art world. However, the issue is: why do you want to participate in the system of exploitation? Of course, you can draw distinctions between a migrant worker and an artist, but I’d argue that the distinctions you wish or want to draw are the same that make art something that supposedly stands beyond the economy.

I recall asking Djordjević why artists even in socialist Yugoslavia didn’t support a rebellion against this exploitative system of the arts, and he said because they believed in this system, they don't want to question the system—however, I believe we need to question the system. I'm not against artistic practice but I’m against the art system and its exploitation of labor. Why does the art system have to be exploitative? It doesn’t have to be, and it is on us to raise these questions and to say no. I think if we know and keep turning a blind eye and keep finding excuses, we won’t get anywhere—and no, we don't have to do endure this, we can create a different system. It is on us to create a different system and implement fair, equitable working conditions for art practice.

I don’t have a definite image of a new system of art production since I deeply believe this is a collective political effort that is already taking place through various initiatives that are invested in a struggle to create a more equitable system for art production, curatorial hotline being a case in point, or the work of W.A.G.E. (Working Artist and the Greater Economy), another one. Nevertheless, I think that any efforts directed towards a new system for art production need to be based on a recognition of artistic labor as work and that such work enjoys all necessary labor protections and is also being properly remunerated. Now, you might say this is a revisionist idea since I often call upon Federici’s Wages Against Housework. Federici points out that demanding a wage for housework is a political perspective, not a goal in itself. In other words, the point is not that an actual wage gets paid but that by demanding a wage for housework one would achieve to show the absurdity of paid work and to bring down the capitalist mode of production where we wouldn’t have to worry about wages. I, however, also think that at present we need to be pragmatic and that demanding fair working conditions and remuneration in contemporary art practice is a necessary political goal. Or, as I said already, ‘until an emancipated understating of art becomes our reality and while we must engage in eliminating the capitalist compulsion to work to live, we should in the meantime demand wages for art work.’

SP: Joining you on the question of what is to be done: of course, we will not be able to change the art systems and stop exploitation in arts—and everywhere else—tomorrow. For this, as you say, profound political and economic changes must take place worldwide, and of course, we also have to play on that field to make them happen sooner. In the meantime, what we can already do today is: analyze and rethink our own agency, practices, modes of production, and ethics; be strategic; influence what we are in power to change on our level; work collectively; bring awareness about these issues to the others. We should be constantly questioning the functioning of the art systems, its automatisms, and our own functioning and automatisms, to be able to detect what we wish not to reproduce. When in the position of power, we should be extremely attentive to how we can provide fair working conditions—economically, politically and emotionally–wise, and how we can rethink established hierarchies, redistribute power and resources. We should develop our empathy in order to understand how the participants of the processes that we initiate live them through. When not in the position of power, we can find ways to build relations horizontally and to create solidarity and mutual support in action. We should be both transparent and strategic when institutions or arts-related organizations and companies are abusing power. We should not be afraid to call out the abusers, individually and collectively, and should have the courage to refuse abusive proposals. In a long-term perspective and on a broader scale, I think that the biggest challenge in the arts—and not only in the arts, by the way—is to overcome individual ambitions, which comes along with sacrificing some of the advantages that we’ve already gained or can potentially gain, and to get organized collectively in order to re-humanize our field, re-become a society, rather than being disparate groups of competing individuals. Which, of course, the system prefers us to be.

Authors’ bios:

Katja Praznik is Associate Professor in the University at Buffalo’s Arts Management Program/Department of Media Study. She is the author of Art Work: Invisible Labour and the Legacy of Yugoslav Socialism (University of Toronto Press, 2021) and The Paradox of Unpaid Artistic Labour: Autonomy or Art, the Avant-garde and Cultural Policy in the Transition to Post-Socialism (Založba Sophia, 2016) that she published in her native Slovene language. She teaches courses related to the political economy of the arts, cultural policy, and labor rights in the context of contemporary arts production and management. Her research has been published in academic and other journals, such as Social Text, Historical Materialism, and KPY Cultural Policy Yearbook, and in exhibition catalogues and edited volumes, for example in Reshape: A Workbook to Reimagine the Art World (Flanders Arts Institute, 2021), City of Women Reflecting 2019/2020 (City of Women, 2020), and NSK From Kapital to Capital (Moderna galerija, MIT Press, 2015).

Sasha Pevak is an interdependent art worker and a PhD student at the University of Paris 8. They are interested in the political nature of art, its infrastructures, and the inner workings that lie beneath the surface. In a practice that is pragmatist, sensitive, and at times tinged with nostalgia, they look to question the boundaries between different fields of art production, and to introduce multiple subjectivities by mixing individual and collective narratives and emotions. They experiment with forms of collective work and social situations that allow to collaborate, both intellectually and emotionally, on developing the meanings of writings, discourses, artworks. Sasha Pevak previously collaborated, among others, with the National Institute for Art History, le Frac Île-de-France, DOC!, Galerie Poggi, la FIAC in Paris, ENSA & La Box in Bourges, ESADMM & Manifesta 13 in Marseille, HISK in Ghent, Garage Museum, 2nd Garage Triennial of Russian Contemporary Art, Moscow International Biennale of Contemporary art, and CCI Fabrika in Moscow. They are part of the teaching team of ENSA Bourges, the IESA in Paris, Sreda Obuchenia in Moscow, and a visiting lecturer at the University of Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne. They contributed to the following magazines: The Garage Journal: Studies in Art, Museums & Culture, Marges, Optical Sound, Switch (on Paper), and others. With a group of art workers and in the wake of the COVID pandemic, Sasha Pevak initiated curatorial hotline, a solidarity platform where art workers can find peers to discuss their practice and thoughts in a non-productive situation, as well as share experiences of work in contemporary art. The initiative seeks to foster solidarity and social links, and an overcoming of general isolation induced by the pandemic. In 2021, in collaboration with Yulia Fisch, they launched an itinerant study group Beyond the post-soviet.

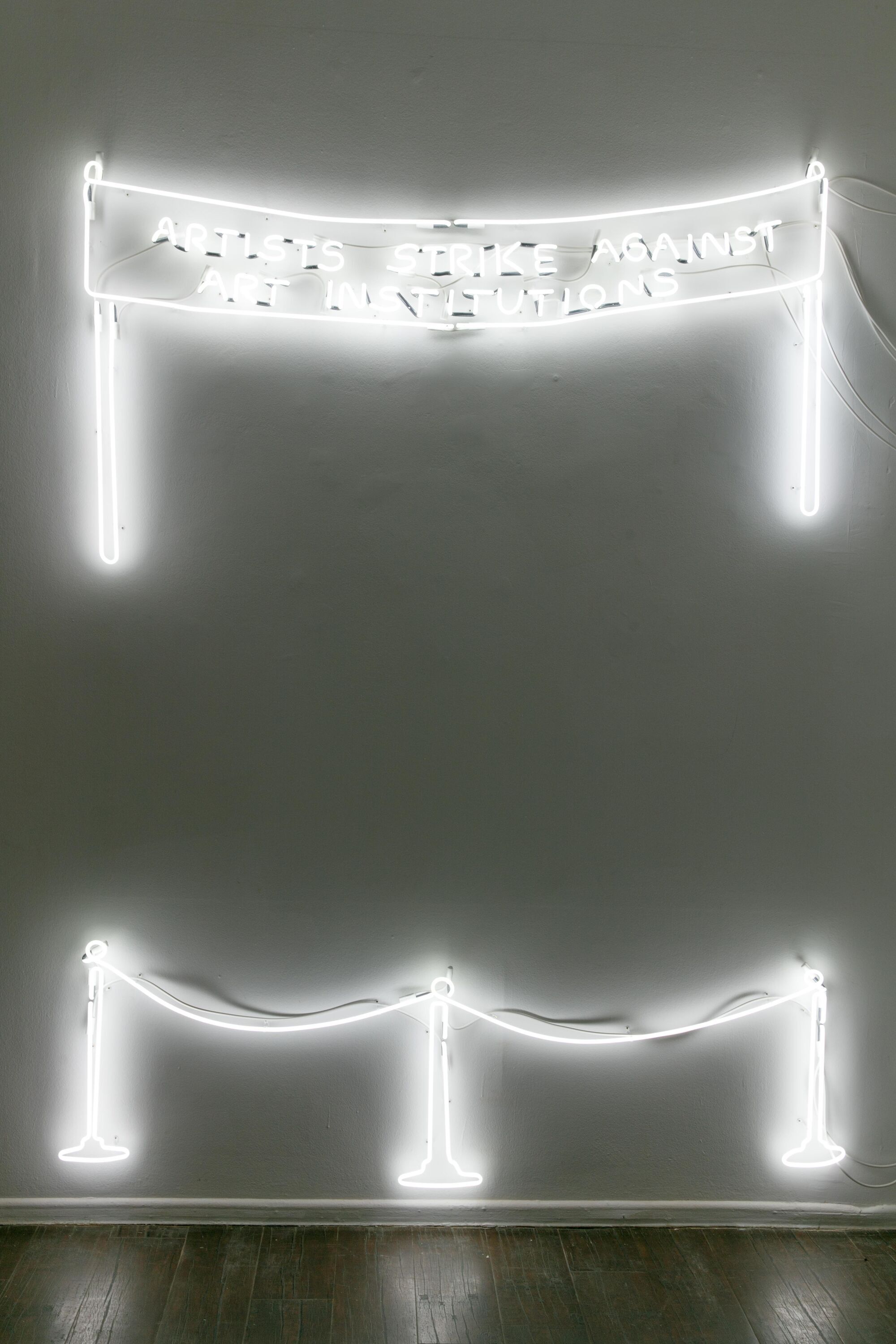

Image credits: Arseny Zhilyaev, The Monotony of The Pattern Recognition (2021) (courtesy of Ivan Novikov-Dvinsky / Moscow Museum of Modern Art).