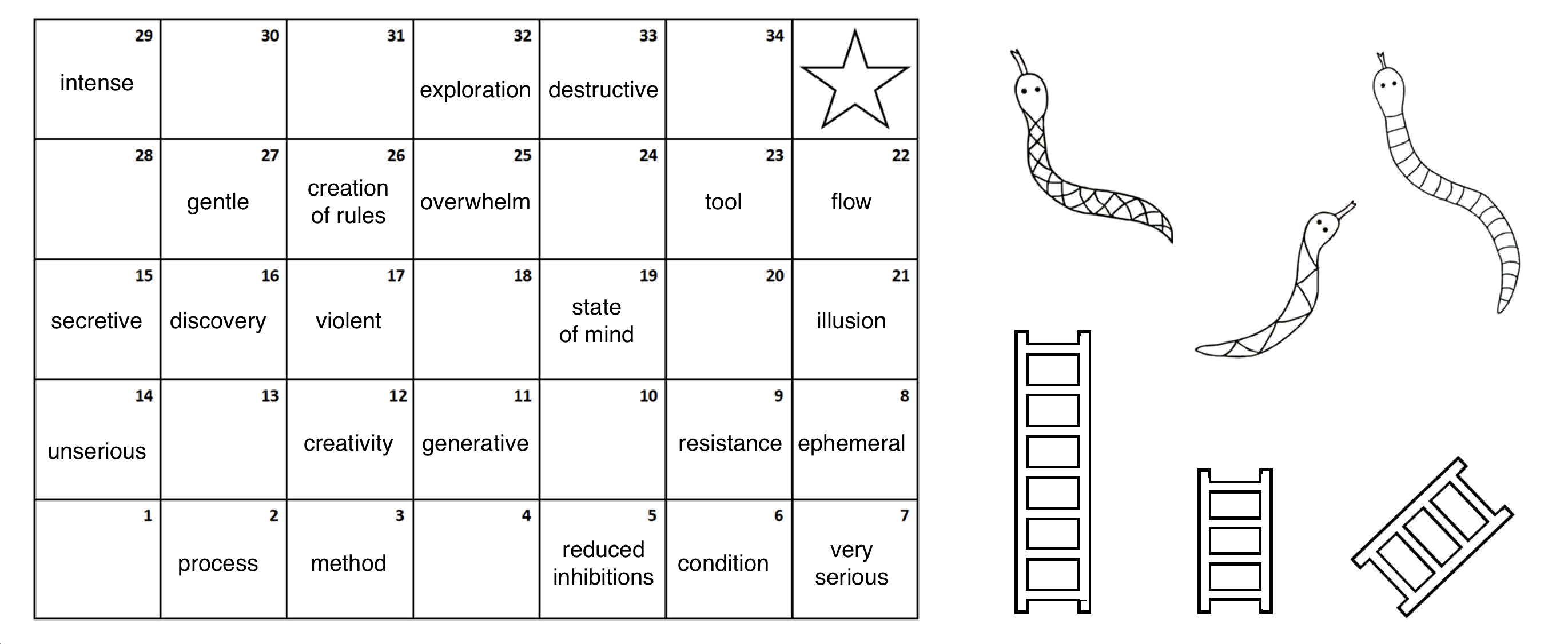

CfP. Method as Play / Play as Method

In this special issue of The February Journal, edited by Anisha Anantpurkar and Pasha Tretyakova and to be published in spring 2026, we are playing with the idea of what it could mean to play as researchers.

Much academic work focuses on the formation of cohesive structures. Research output is influenced by the way we are taught to conceptualize what we are researching. Perhaps that is why scholars often describe play as paradoxical: our tools are oriented to thinking productively. But even the streamlined scientific process of knowledge production is one of assemblage where parts play with each other (Latour 2005). While standardized rigorous methods used to hold a stamp of approval, an authority that comes with attaining expertise, we see increasing resistance to traditional ideas of expertise today. These resistance efforts emerge on a spectrum, from decolonial thought challenging systems to influencers, politicians, and online commentators playing with public sentiment to establish dominant narratives. New methods for thinking this moment are needed. Play can be subversive, creative, and fun, and it can be dangerous, scary, or even harmful. They may not be disparate processes. Instead of thinking contradictions and hierarchies as categories, can play shift the focus to the interactions, the interdependencies?

We approach play not just as an activity but as a generative process, a space of encounter, instability, and emergence. We want to think of method as a process, as a space of play—of role- and code-switching, of subversion, of difference. What does it mean to play as knowledge makers? Where does play emerge for you?

Gregory Bateson observed that ‘play is not the name of an act or action; it is the name of a frame for action’ (Bateson 1979: 139). His student expanded this idea: ‘Play is easy to recognize but impossible to define… it is meta to “ordinary”” activities… but especially, it is meta to the activity of defining’ (Nachmanovitch 2009: 15). Roberte Hamayon (2016) similarly speaks of the ambiguity between fiction and reality at the heart of play. The entanglements of ‘reality’ and ‘fiction’ are at the core of both emancipatory and artistic processes. How can play destabilize the structures of academia and art, research and practice, scientific and unscientific knowledge, towards critical perspectives?

Bateson also posits that play breeds heterogeneity (Nachmanovitch 2009: 11–12). He views play as a dynamic space where differences are not barriers but the foundation for collaboration. What is the role of interplay of differences in collaboration? Naisargi Davé (2023) writes: ‘Let’s be honest. There is no shortage of the opposite of indifference in our world, which is the desire for difference—finding, wrangling, and utilizing it. And where has that gotten us? Anthropology? Heterosexuality? Capitalism? Empire? Friends, I think we can do better’ (p. 1). So, how do we approach difference without making it the center of our lenses, as anthropology and colonialism have? Davé (2023) argues that ‘indifference is the posture of immersion, side by side, rather than face to face’ (p. 1). How do we engage in play with others? How do we sit, stand, and move through spaces of difference? Who gets to play, and for whom are conventions the only way in?

Many say that in order to make art, you need to be in a state of play.

The director tells the actors: ‘Let’s play this scene.’

The collaborator says: ‘Let’s let things flow. Let’s play more with that object, let’s play more with form.’

An actor plays a role, plays with a character, plays a person. Then they might go home and role play.

The dance instructor says, you’ve been taught the technique—now it’s about how you play with it.

We can play with gender, assembling our own. We learn sexual play—some is deemed ‘natural,’ some ‘unnatural.’ We learn to play [with] ourselves.

Play can be a tool, a process, a mode to understand oneself.

We are not seeking resolutions. We seek explorations—an engagement with the process. Moving beyond play as a game, ritual, or phenomenon, we encourage looking at play as a force within doing, making, feeling, thinking. We are interested in what play generates and what it destabilizes. We are interested in where you find play within your processes, whether it's a moment or a millennium, and why you call it so.

Here is an approximate list of what we would be interested in thinking about with contributors:

– playing with and against scholarly and other types of canon;

– mediations on research methodologies, process, and academic writing;

– juggling identity—gender, race, class, caste, ethnicity, personality, desires, ethics, and moving through it all;

– explorations of sites of manifestation, expression, emergence;

– playing with difference, indifference, intimacies, and corporealities;

– play in queerness, ecosexuality, bestiality;

– play as knowledge in Science and Technology Studies;

– struggle, denial, rejection, subversion as play;

– the risks of play(ing) and play in the face of threat;

– playful perspectives on rigor, rigorous methods, standards;

– improvisation, experimentation, investigation;

– inversion, humor, clowning & fooling in politics and beyond.

We invite scholars, artists, and practitioners to play with these questions and see what emerges when placed in conversation with one another. We welcome academic articles, reflexive and visual essays, artistic pieces to be published/documented in film, photo, or audio format. We look forward to playful formats and genres.

Send us your proposals. Let’s play.

Bibliography

- Bateson G (1979) Mind and Nature. New York, Dutton.

- Davé N N (2023) Indifference: On the Praxis of Interspecies Being. Duke University Press.

- Hamayon R (2016) Why We Play: An Anthropological Study. Translated by Damien Simon. Chicago, HAU Books.

- Latour B (2005) Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford University Press.

- Nachmanovitch S (2009) This is Play. New Literary History, 40(1): 1–24.

To submit a proposal, please provide the following information in English:

- contribution type (e.g., article, visual essay, reflexive essay, data essay, etc.);

- language of contribution;

- title of contribution;

- abstract, maximum 300 words;

- keywords that indicate the focus of the contribution;

- biographical statement, maximum 100 words.

Please send proposals by June 20, 2025, as a single PDF document to info@thefebruaryjournal.org.